For any given hobby, industry, or service domain, the domain in question has its own terminology that needs to be understood before someone can successfully navigate within it. The educational realm is no different and this article will shine a light on the differences between the concepts of ‘critical thinking’ and ‘critical theory’. Although the two terms sound quite similar, the meanings and goals of each are vastly different.

The branch of critical theory that focuses on education is called critical pedagogy. By itself, pedagogy simply means the various approaches of teaching to kids. When you throw the word ‘critical’ in front of the word ‘pedagogy’, you are talking about an entirely different beast. For definitions on critical thinking and critical pedagogy, we’ll turn to the 2017 academic paper Tracking Privilege-Preserving Epistemic Pushback in Feminist and Critical Race Philosophy Classes by Dr. Alison Bailey. Per page 6 of Dr. Bailey’s paper:

Philosophers of education have long made the distinction between critical thinking and critical pedagogy. Both literatures appeal to the value of being “critical” in the sense that instructors should cultivate in students a more cautious approach to accepting common beliefs at face value. Both traditions share the concern that learners generally lack the ability to spot inaccurate, misleading, incomplete, or blatantly false claims. They also share a sense that learning a particular set of critical skills has a corrective, humanizing, and liberatory effect. The traditions, however, part ways over their definition of “critical.” Nicholas C. Burbules and Rupert Berk’s comparison of the traditions provides a useful background for my discussion in the next section. The critical-thinking tradition is concerned primarily with epistemic adequacy. To be critical is to show good judgment in recognizing when arguments are faulty, assertions lack evidence, truth claims appeal to unreliable sources, or concepts are sloppily crafted and applied. For critical thinkers, the problem is that people fail to “examine the assumptions, commitments, and logic of daily life. . . the basic problem is irrational, illogical, and unexamined living” (Burbules and Berk 1999, 46). In this tradition sloppy claims can be identified and fixed by learning to apply the tools of formal and informal logic correctly.

Critical pedagogy begins from a different set of assumptions rooted in the neo-Marxian literature on critical theory commonly associated with the Frankfurt School. Here, the critical learner is someone who is empowered and motivated to seek justice and emancipation. Critical pedagogy regards the claims that students make in response to social-justice issues not as propositions to be assessed for their truth value, but as expressions of power that function to re-inscribe and perpetuate social inequalities. Its mission is to teach students ways of identifying and mapping how power shapes our understandings of the world. This is the first step toward resisting and transforming social injustices. By interrogating the politics of knowledge-production, this tradition also calls into question the uses of the accepted critical-thinking toolkit to determine epistemic adequacy.

I think most people will find Dr. Bailey’s definition of critical thinking not only to be reasonable, but also a desirable foundation for learning in our public education institutions. Critical thinking, with its focus on epistemic adequacy, means that students will be able to demonstrate mastery of skills and subjects. As a real-life example, if you need your car fixed, you expect the mechanic to have the skills and knowledge to diagnose what’s wrong with your car and fix it. So, what does critical pedagogy offer? Well, in Dr. Bailey’s own words, the ‘critical learner is someone who is empowered and motivated to seek justice and emancipation’. In other words, mastery of subjects such as algebra and biology is secondary to activism. On top of that, truth doesn’t matter and the last sentence of the excerpt explicitly calls out that critical theory questions the methods of critical thinking. I think it’s pretty obvious that critical theory stands on a very shaky foundation. Next time you drive over the Mackinac Bridge, be thankful that the builders of the Mighty Mac accomplished their tasks many years before critical pedagogy started infiltrating education.

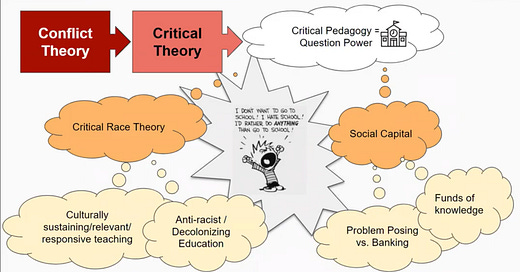

At this point, critical pedagogy has been making inroads into the teaching colleges for decades. A quick YouTube search of “what is critical pedagogy in education” led me to this gem of a video by Dr. Angela Macias: Introduction to Critical Pedagogy. In the following slide, Dr. Macias links critical theory to critical pedagogy to culturally responsive teaching.

Culturally responsive teaching is a major component of Social Emotional Learning (SEL). Isn’t it interesting that the hottest topic in education today, SEL, has roots in neo-Marxian critical theory? I think it’s safe to say that SEL will not be righting the ship in the direction of critical thinking.

Critical theories are not appropriate for K-12 learning environments. When it comes to critical thinking versus critical theory in your child’s schooling, be on the lookout for assignments that use emotion to enforce a particular viewpoint, doing so in the absence of a counter argument. That could indicate that a power dynamic is at play and a particular ‘correct’ viewpoint is trying to be ingrained.

Other references for this article: